|

- Home

- About Us

- Join / Donate / Volunteer

- Speakers / Events

- Home Tour / Walking Tours

- Garner House / Rentals

- Archives / The Vault

- Resources

- Archives Research

- Stories ofthe East and West Barrios

- Citrus Industry / Fruit Crate Labels

- Claremont Treasury of Music

- Claremont Passionate for Trees

- Claremont Trees Emergency

- Consultation: Historical Preservation

- Education: Third Grade Program

- Gabrielino Tongva

- Historical Preservation

- Lounge: Online Publications

- Our Town Live

- Preserving Our History

- Properties For Sale - Historic

- Oral History - Karl Benjamin

- The Mills Act

- Videos

- Shop

- Contact

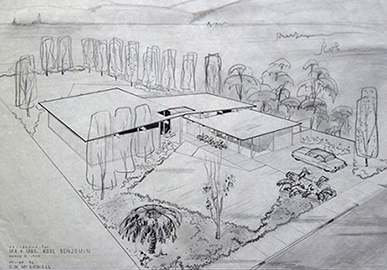

Interview with Karl Benjamin September 21, 2009  I had no interest in art whatsoever as a kid. But when I graduated from college, I wanted to be a writer and so I got this job teaching sixth grade, [at] Bloomington, over in Fontana. That was just about the time, 1949, when abstract art started to get in LIFE magazine. And some of the stuff was suspicious to me, and then it gave me the confidence, because I saw that those kids in Bloomington—who were from a very poor social economic class—were doing stuff that was in LIFE magazine, in our news. You can believe me, it scared me.

Do you feel there are different periods in your work? Well, I have three or four themes. It hasn’t been a development like that [motions with hand], but these pretty good themes seem to pop up every six months to a year and half. Often, it comes like you have it up to a bunch of paintings in a very high heat color, very complicated, like these [motions to painting around him]...these are complicated. So the next batch of things probably would be simple and restricted in color. It’s alright, Picasso said to paint green until you can’t stand green anymore and then paint something else. It’s still making visual objects. And when someone says, “What is it?”, the person is not familiar with art. It’s a painting. It’s a visual object; you look at it and say “What does it do to you?” Do you consider some of your work very architectural? Oh, it is. I think it is. I think if you’re brought up in Chicago, in the middle of a city, you probably have a visual impression in your life. I also think there are a lot of paintings like that one over there [motions to painting] that always reminds me of buildings. When I looked out my bedroom window, I looked at the apartment building across the way, and there’s a wall with a bunch of windows—the city wall, somewhere. But somebody else entitled it, “Graveyard.” You live in a Fred McDowell designed home. How did Fred and you meet? He had just gotten to Claremont, and it’s one of the first houses he did. We were the same age; we were close friends at least. I didn’t know anything about architecture. My parents were going to have a house—my dad was a doctor in Santa Barbara, and they had very conservative tastes. They wanted me to have a proper house, and they didn’t believe that there were no walls, just windows in the back! But then after a while they got to understanding, and so they built a house just like it in Santa Barbara, based around a big old 200-year-old oak tree, which was in the middle of it. “Claremont is not New York or Los Angeles…It’s not even Kansas City!” –Karl Benjamin Despite this, was there a creative consciousness in Claremont? There was, right after the war [WWII], but that happened in a lot of places after the war. I was a member of that generation. Those were the greatest years, those post-war, early 50’s, late 40’s. Those were the older, more serious, more turned-down years, no matter the subject matter. That happened in art, and it happened here [Claremont] in art. That’s why I came to Claremont, from Redlands. Who were some of the Claremont creatives/artists you frequented? There was Paul Darrow, who was here for a long time; he’s in Laguna now. Jack Zajac was here. Sue Hertel was a really good long-time artist. Bob Frame, Arnie Schiffer, there were really a number of guys who had art careers. Harry and [Marguerite] McIntosh had a little cabin [ceramics studio with Rupert Deese]on Foothill before the [construction of the Sheets designed Pomona First Federal] bank. Explain Hard Edge vs. Abstract Classicism vs. Abstract Expressionism. Hard Edge got started the late 50s, and I hate that word. It doesn’t mean anything. What’s a soft edge? Monet? To write about something, you have to find a word, so unfortunately I don’t think that was a very good word. Abstract Classicism was another one. Someone had a show in London, and irrationally corporate called it Abstract Classicism. Well, it was good for your career, because you had a name now, but it didn’t mean anything. But you take it in context. In any art, there’s the romantic and the classical. It’s always kind of torn between those two poles. So there was Abstract Expressionism, which was accepted for wild painters, which were brand new then, and Abstract Classicism, which was opposed to expressionism. But it balanced out equally. What would you call your art? It would depend on who I was talking to, what term they would understand. I would just say I’m a contemporary artist, but again I’m not an objective painter, because these objects—they’re objects! You know, I’m not abstract; I just call myself a contemporary painter. What was the pivotal show of your career? This is hard to believe, but if I were to pick out one show, I get the biggest kick out of this one right now at Claremont Graduate University (2009). I’ve been here the whole time, and 55 years later, I’m still two blocks away. And the thing is about that show, thanks to David Bagel—the show that started by my going to see David—is that I had these eight paintings that I did 30 years ago and I’d never seen them. So I said, “Let me have one of the galleries, and we’ll put up those eight paintings,” because I felt that it would be good in one piece. They weren’t able to get any dealers to put them up, because they insisted they could sell just one, and they’d say, “Who’s going to buy eight dark, simple paintings?” So he said, “Oh, fine, but why don’t you take the other two and do something opposite?” It’s kind of my two poles—the really simple kind of stuff and the really complicated things. Art and People: The Rainbow Lesson. Explain? One more thing with those kids you’d asked the question before about, how art related to people. After they were past the mountains and things, I could give them an assignments, and they could all do it their own way. I could pass out paper, and say, “Fill your paper with a rainbow.” What’s a rainbow in your mind—you think of yellow, green? But you’d get greens and purples, you’d get browns and grays, and of course you’d get a regular, honest to God rainbow. But just to show you the different innate [difference]—they’re happy with their rainbow. There’s no conflict in their mind about that. There are a lot of lessons in that.  |